When it launched the Reflex, Ansco was a well-established entity in the photographic industry. Founded in 1842 as E. Anthony & Co. by Edward Anthony, the company later merged with Scoville Manufacturing to form Ansco. In 1902 they relocated to Binghamton, New York, the home of one of their photographic paper manufacturing facilities.

In 1914, Ansco settled a roll film production patent infringement case against Eastman Kodak. The settlement, for 5 million dollars, was relatively small compared to the economic damage done to Ansco. Previously known as the largest suppliers and distributors of photographic supplies in the United States, Ansco was now in second place to Kodak’s first place.

The move to Binghamton also shifted Ansco’s focus from distributing all photographic supplies to focusing producing their own film, paper, cameras and accessories. The money to be made in the industry at the time was in film, paper and processing. Ansco produced and developed a number of well-known and respected films and papers at its Binghamton facilities, right up until they ceased production of consumer films in 1977.

Photography, as a new hobby and obsession, fell into two categories: amateurs taking snapshots and professionals who worked with large view cameras in studios. Ansco produced cameras for both groups. Their amateur line of cameras ranged from simple box cameras to inexpensive scale-focusing roll film and a fixed focus twin lens camera. Its studio view cameras were large wooden affairs that used 4”x5” and 8”x10” film and were well respected and widely used by professional photographers.

Their cameras, however, were usually one-time purchases. Professional photographers might purchase an additional lens or two but amateurs, with their fixed-lens cameras, had no such option. Ansco’s bottom line came from purchases after the camera: film, processing, prints and more film.

Financial Struggles

Ansco, founded in 1842, was one of the earliest photographic equipment and supply manufacturers in the United States. Despite an early start and a patent that should have secured their role in the marketplace, Ansco struggled for years to recover from the significant financial blow Kodak delivered when they entered the market in the late 1880s. In 1928, Ansco merged with Agfa (a German company).

The German parent Ansco provided money, technical talent, and access to patents. Later the same year, Agfa merged with other German-owned chemical firms into a Swiss holding company, IG Chemie, which in turn was controlled by the German conglomerate, IG Farben. The parent corporation’s name was changed to American IG Chemical Corporation and eventually to General Aniline & Film.

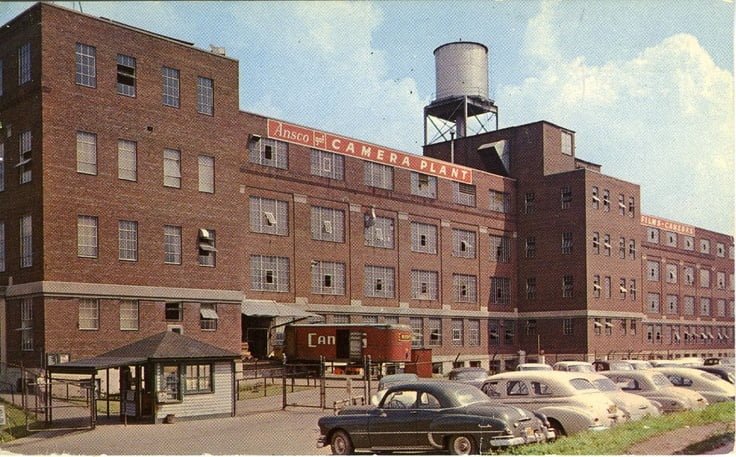

Flush with foreign cash, Ansco expanded its production facilities. They built a new film production plant, a new camera plant and acquired buildings as part of unprecedented growth. During this same time, they won several awards for developing infra-red and high speed black-and- white films.

Ansco was on track to financial success, having two consecutive years of record earnings in 1938 and 1939. Efforts were under way in 1939, for instance, to increase earning power by fully merging with General Aniline & Film (which owned 81% of Ansco at the time).

Despite its increased size, Ansco remained a distant second to Kodak. And the onset of World War II had a huge impact on Ansco.

World War II

General Aniline and Film, the American parent of Ansco, came under close scrutiny by the U.S. government with the Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939.

Ansco saw the writing on the wall immediately: Ernst Schwarz, president of Agfa Ansco Corp., renounced his German citizenship and was sworn in as an American citizen at noon the same day. Over the next several years, General Aniline and its subsidiaries replaced German-born officials with native-born Americans in a vain attempt to forestall eventual nationalization. John Mack, a friend of President Roosevelt, replaced D.A. Schmitz, who resigned as president on Sept 23, 1941. In 1942, the US government seized and nationalized Agfa-Ansco as enemy property.

Like many other companies, Ansco produced bomb fuses, sextants, rangefinders, film, cameras, airplane instruments and other products for the US war effort.

In January 1942, Leopold Eckler, and American citizen since 1936, and four other executives were suspended by the Treasury Department because they “personified the domination of the company by the German dye trust (IG Farben).”

Ansco workers were baffled by this move and petitioned the Treasury Department to reinstate Eckler, to no avail. A few weeks later James Forrestal was named acting manager of the Agfa Ansco Division.

By this point, General Aniline has lost nearly a dozen key employees through resignation or suspensions. Ultimately, their effort to “try to keep on rolling under [their] own momentum” failed.

In 1943, Ansco dropped “Agfa” from their official name.

Post World War II

Ansco was under US government supervision for more than 20 years, until it was finally sold in the mid 1960s.

The long delay was due, in part, to the Red Scare of the 1950s. In July 1954, a retired General Aniline executive warned a Senate Judiciary Committee that “secrets developed by General Aniline and Film … would be passed behind the Iron Curtain … if foreign control of the company were restored.” Prolonged court cases over the ownership of General Aniline shares also tied up its eventual privatization.

At the end of the war, Ansco immediately announced the return of some of their popular, pre-war cameras (Cadet, Clipper, Viking 63, Speedex Junior and Speedex 45) along with two new models: the Reflex and the Panda.

The Ansco Reflex, as it was called in those early announcements, was promised after reconversion of the camera plant. Reconversion, however, was not a quick process. The camera plant, which had been retooled to produce military optical devices, needed new machinery and tooling to produce the Reflex.

Ansco faced significant competition in the marketplace. Kodak, their nearest competitor, had 27,000 employees even after post-WWII downsizing. Ansco, on the other hand, was one tenth Kodak’s size at 3,000 employees. Kodak was able to invest 100 million dollars in new factories and facilities in the years immediately following the war; Ansco invested only 5 million.

The biggest burden, however, was supervision by the Alien Property Custodian. Because they were owned by the government, they lacked ready access to equity capital. Further, what money they could secure, from insurance companies and banks, was “spent only after time-consuming study and deliberation.”

Ansco’s management, their president and board of directors, were extremely cautious about making expenditures. Decision making took far more time than it did with their competitors: checks were more thorough and, in trying to avoid mistakes, they moved very slowly.

Ansco, by admission of Jack Frye, chairman of the board and president of General Aniline, was “never in the strict sense a camera manufacturer. It lack[ed] facilities for grinding lenses, making shutters, and molding cases.” It purchased component parts, like the Wollensak shutter and lens in the Reflex, from domestic manufacturers.

Given the significant challenges Ansco faced, it comes as no surprise that it was not until December 1946 that the camera plant was able to start production on the Reflex.

On top of all that, all photographic products faced a 25% federal tax, which hampered the return of the entire industry. Products had to be priced to make a profit; the tax drove those prices out of reach of many ordinary Americans.