Value is always in the eye of the beholder, so the value of your Reflex depends on what buyers want.

Value is always in the eye of the beholder, so the value of your Reflex depends on what buyers want.

When Ansco announced the Reflex in 1945, their ads in trade journals claimed that the camera was “6 years old”. Those ads showed an all-black Reflex with many features in common with the production model.

There is not a lot of evidence to support the claim. Government records don’t mention the Reflex until 1945. Ansco spent most of the war developing and producing war materiel.

A factor in the shortage of photographic equipment and supplies was the conversion of many manufacturing plants to the production of other war equipment. For example, Eastman stopped making cameras in 1941–1942, and began again only in a limited way in 1943. Ansco stopped soon after Pearl Harbor and throughout the better part of the war produced no photographic material except paper and film.1

In 1943, the Army Pictorial Service organized the Pictorial Engineering and Research Laboratory (PERL) to rede-

sign, improve, and develop better photographic equipment.

For the most part, PERL projects consisted of short-range modifications, improvements, or adaptations of existing items. The actual development work PERL accomplished either in its own laboratory, or through contracts with commercial concerns.2

Yet the Reflex did not spring from nothing in 1945. There had to have been some work in preparation. Ansco had two successive years of record earnings in 1938 and 1939. Flush with cash, it makes some sense that they would start to develop a camera to compete with the very popular Rolleiflex.

The answer to that mystery may be this prototype.

Ansco announced the coming Reflex in trade journals like the North American Retail Druggists (N.A.R.D.) Journal, Photo Trade News and National Photo Dealer. The ad listed seven features of the new camera and claimed improvements suggested by U.S. Army Signal Corps. PERL was a part of the Signal Corps and may have provided feedback to Ansco about the Reflex. I’ve not found direct evidence to support that yet.

Ansco, and General Aniline and Film, came under close scrutiny of the government with Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939. In 1942, the U.S. government seized AGFA-Ansco as enemy property. The firm dropped AGFA from its name in 1943. This prototype, clearly labeled AGFA, was likely developed before the name change.

AGFA-Ansco lost a significant number of German and naturalized employees of German descent between 1939 and 1942, including key engineers and machinists. It’s not unreasonable to think that Reflex development began in 1939 and petered off as key engineers were dismissed. The intelligence gap created presented problems for General Aniline and Ansco in other areas, so the delay between announcement and production makes a certain amount of sense.

There are several details about this prototype, aside from the most obvious, that are immediately notable:

Other, less obvious exterior differences are:

There are a few details on the inside worth noting:

Last the everready case is stamped with the Agfa diamond logo on the front, just below the taking lens.

It’s clear from the numerous small differences between this and the production models that it’s a prototype. Exactly when it was made is hard to pin down but an abundance of clues point to sometime before 1943.

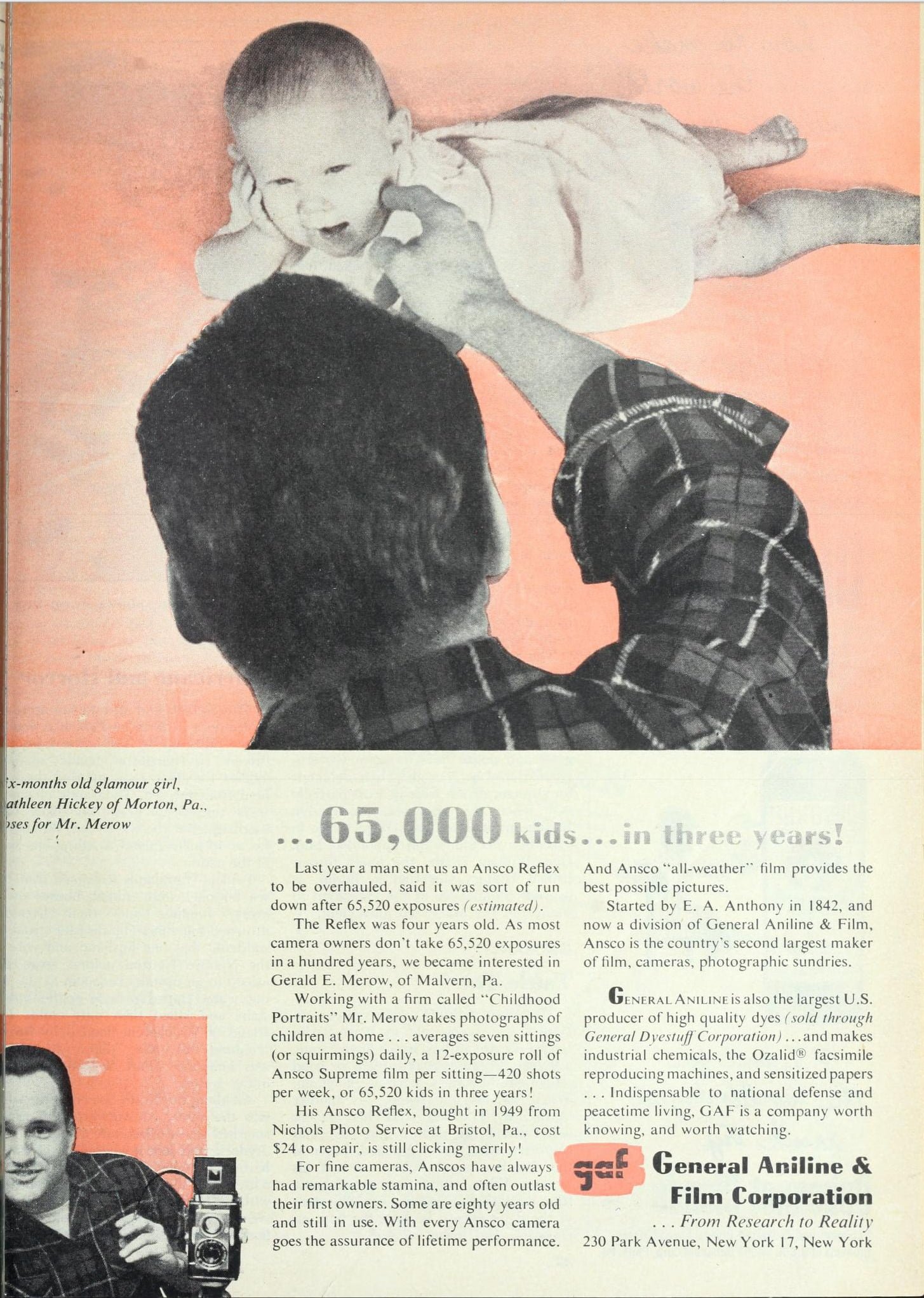

Even though Ansco had stopped making the Automatic Reflex, this story was interesting enough to turn into an advert for General Aniline. The estimated 65,520 exposures may be an exaggeration but it’s an interesting bit of history.

Here’s the copy from the advert:

65,000 kids … in three years!

Last year a man sent us an Ansco Reflex to be overhauled, said it was sort of run down after 65,520 exposures (estimated).

The Reflex was four years old. As most camera owners don’t take 65,520 exposures in a hundred years, we became interested in Gerald E. Merow, of Malvern, Pa.

Working with a firm called “Childhood Portraits” Mr. Merow takes photographs of children at home … averages seven sittings (or squirmings) daily, a 12 exposure roll of Ansco Supreme film per sitting — 420 shots per week, or 65,520 kids in three years!

His Ansco Reflex, bought in 1949 from Nichols Photo Service at Bristol, Pa., cost $24 to repair, is still clicking merrily!

For fine cameras, Anscos have always had remarkable stamina, and often outlast their first owners. Some are eighty years old and still in use. With every Ansco camera goes the assurance of lifetime performance.

And Ansco “all-weather” film provides the best possible pictures.

A unique and probably one-of-a-kind lens showed up on eBay in early 2018. The 83mm f3.5 Ansco Anastigmat lens (which is actually a Wollensak) was mounted in a brass barrel fitted with an Exakta mount.

The first auction posting showed just the lens. A subsequent post showed the lens mounted on an Exakta Varex.

No details, other than the photos, were available about the lens. The seller didn’t know anything of its provenance, so who or what prompted someone to make such a thing are unknown.

Ansco used Wollensak’s new Rapax shutter and a Wollensak lens in their Reflex. Ciro used the same shutter, and essentially the same lens, in several models of their Ciro-flex camera.

The Rapax featured flash synchronization from the start, according to an announcement in the May 1945 issue of American Photography. For whatever reason, Ansco didn’t implement the flash sync feature on their first round of Reflex cameras.

The new Rapax shutter, announced by Wollensak Optical Co., Rochester, features built-in automatic flash lamp synchronization and shutter speeds from one second to 1/400 second. A single click-stop allows the use of any popular flash lamp by selection of either a 5 or 20-millisecond position in the larger size shutters. 5 millisecond speed only with the smaller size shutters. The Rapax shutter is mechanically tripped by hand, thus the electrically controlled flashing of the lamp is the only drain on the battery. Flash peak and maximum shutter opening are synchronized by a precision built-in gear train. Entire production of the new shutter is being used at present by the armed forces.

The lack of a dedicated flash sync, although common on many cameras at the time, was frequently pointed out in the press at the camera’s introduction. Ansco added flash sync and offered a retrofit for existing owners. Based on one sample, the retrofit was a moderately labor intensive process.

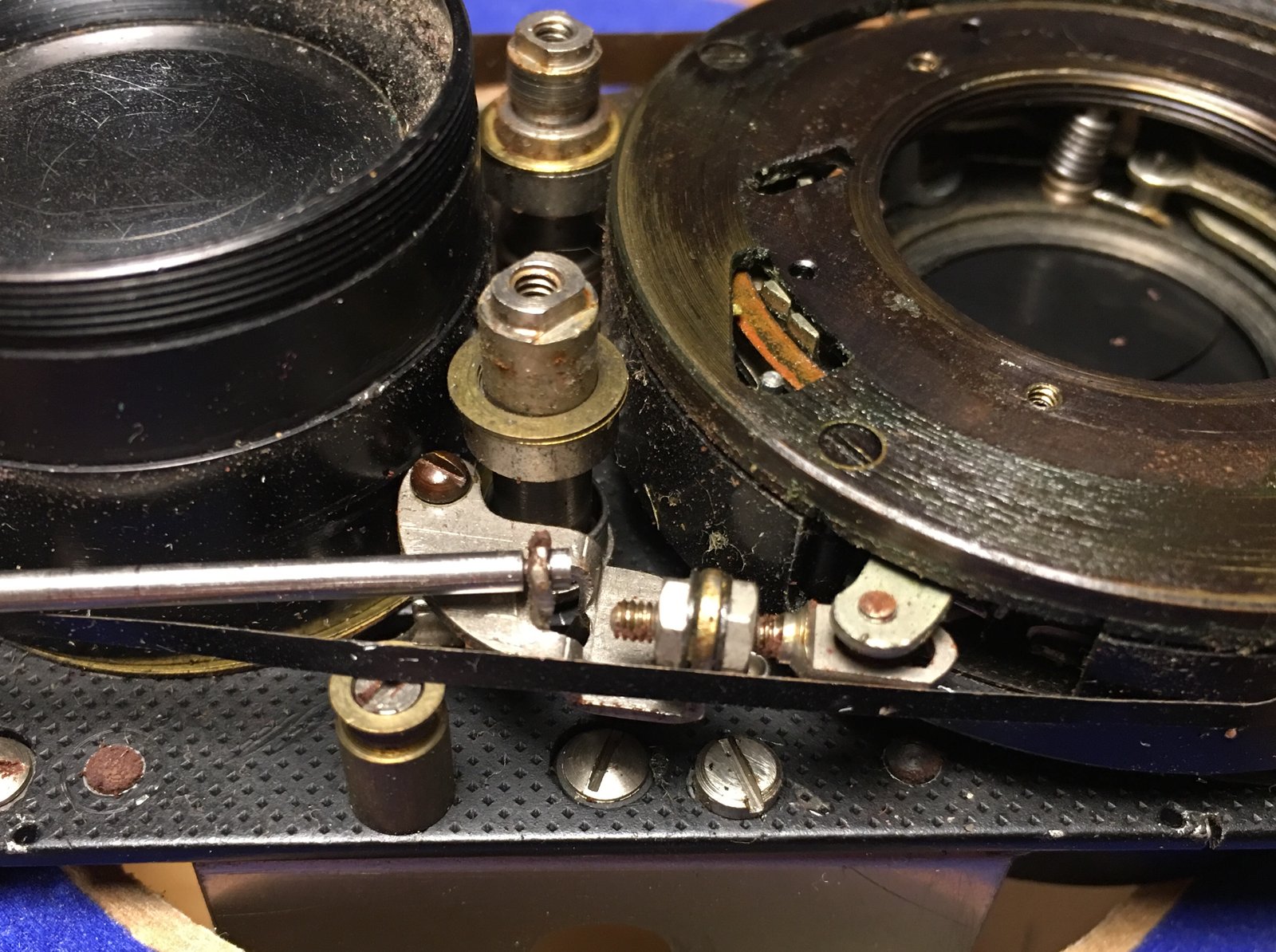

The inner workings of the Reflex were reasonably well documented at the time of its release. Ansco released photos of the camera parts and assemblies to photography magazines, along with details of how the camera was assembled.

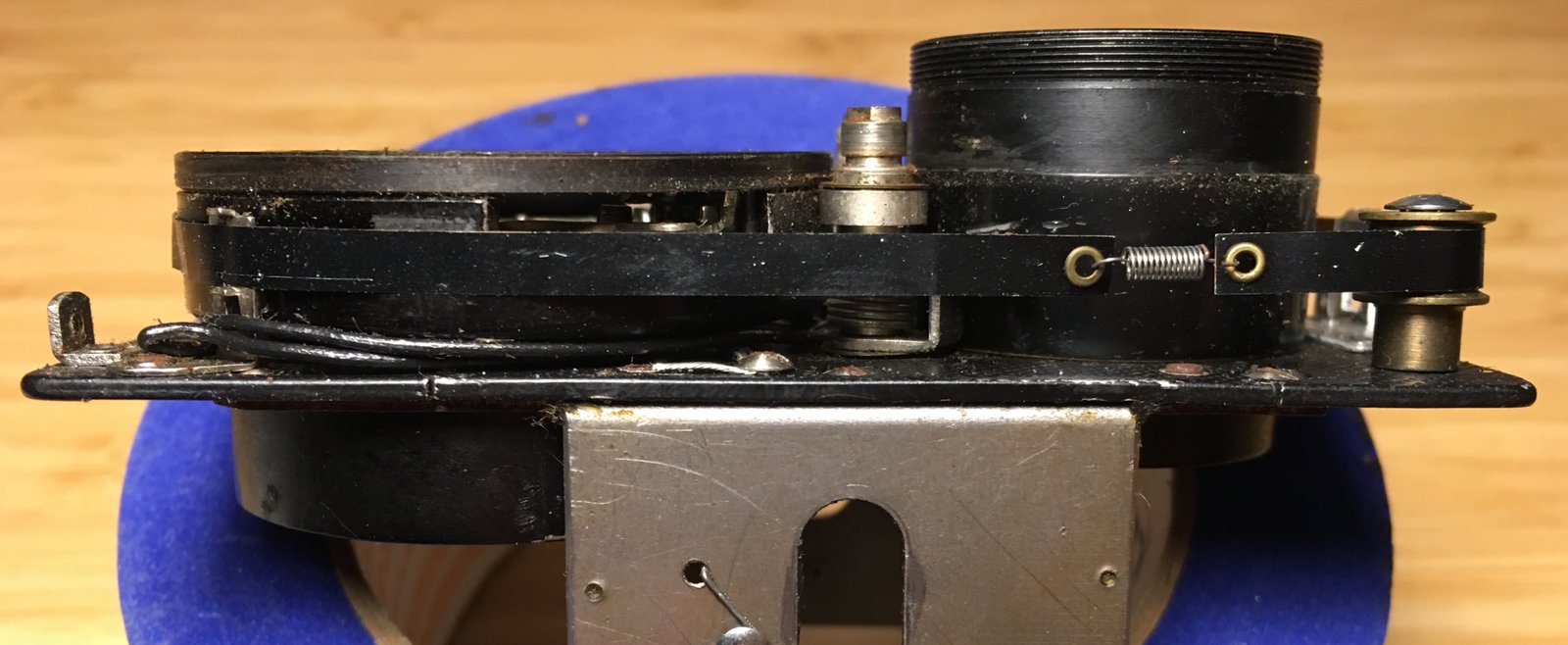

The camera itself is relatively simple. An aluminum casting makes up the main part of the body. The casting itself is lightweight.

Four brass guides, two on each side, are pressed and screwed into each side. A steel guide, attached to each side of the lens panel, glides along the V grooves of the brass guides. The bearings are greased, a grease that remains in good condition 70 years after it was applied. A cam follower pin, on both sides, engages with the cam in the focusing knob on both sides. Springs on the right side help with the “return” part of focusing.

A Wollensak lens and shutter assembly are mounted on the lens panel. A thin metal belt, attached to the focus lever, transmits the aperture value to the window at the top.

The shutter release mechanism is a little complicated, one that required fine tuning at the factory. The notorious interlock release, on the side of the camera, could do nothing to remedy a jam in the lens shutter itself. Such a jam would render a camera inoperable, like the example in these photos.

This particular Reflex started life as a type 1. Standoffs on the left and right side of the lens acted as guides for the shutter tape. The standoff on the right was drilled out for the flash connector standoff.

A wire, fed into the shutter, is soldered to the release post. Another wire is screwed to the baseplate of the lens panel, providing a ground for the flash sync.

The most tell-tale indicator of this retrofit is the machining of the shutter assembly. It’s clear that the opening for the flash sync is not original: it appears to have been ground into the case.

Inside the shutter, the sync connections are factory original parts. The Wollensak Rapax was designed with flash sync; apparently it was up to the camera manufacturer to decide if they’d use it.

What is clear, however, is how much work went into retrofitting flash sync to existing type 1 cameras. The side panels, along with the overlaying leather covering, had to be removed to gain the access necessary to remove the lens panel from the camera.

Upgrading a type 1 with flash sync requires removing the stamped cover and removing the lens unit from the lens panel. It is a near complete disassembly of the lens mechanism. At $24.50, the cost at the time, owners received quite a good deal.